Gender-Based Violence Is Treated as a Moment

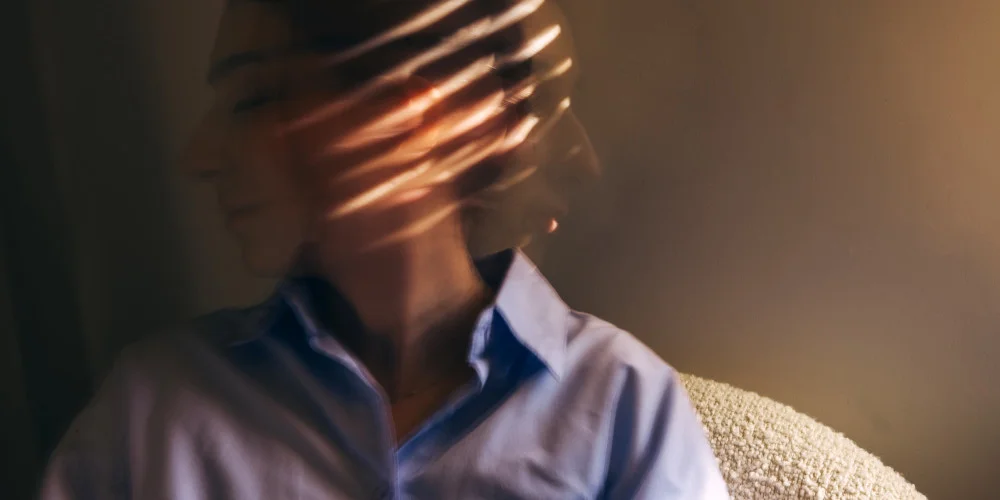

Gender-based violence erupts into the public consciousness in sharp, dramatic bursts. A murder case surfaces, a viral video spreads, a survivor posts her story, or a news outlet features a horrifying incident. For a few days, sometimes a few weeks, the world reacts with shock, outrage, hashtags, and online sermons about “raising awareness.” But awareness is temporary. Outrage fades. News cycles move on. People return to their routines. The survivor, however, does not. Her pain does not trend for only a week. Her trauma does not end when journalism shifts to the next story. Her life does not reset when the world loses interest. She wakes up with the consequences long after the public has found a new topic to rally around.

The public treats gender-based violence as an event rather than a life-altering reality. They prefer the version of the story that fits into a Facebook post, a headline, or a news clip. They like beginnings and endings. They like villains and victims drawn in black and white. They like the idea that justice is swift or that healing is linear. But survivors are left behind in the ruins of everything that happened once the attention fades. They must rebuild while the world moves forward without them. This abandonment is not accidental, it reflects a society that is far more comfortable consuming trauma than supporting recovery.

The Public Consumes GBV Like Entertainment, Then Disappears

There is an uncomfortable truth few people admit, gender-based violence has become a form of public spectacle. People share content, debate in comments, analyse details, speculate about the survivor’s decisions, and pick apart the abuser’s behaviour as though they were discussing a fictional drama. Outrage becomes a form of social performance. People want to be seen reacting correctly more than they want to actually support real survivors. Once the initial emotional rush passes, interest evaporates.

Survivors feel this abandonment acutely. One week, strangers rally behind them. The next, they are left to navigate the consequences alone. The silence that follows public attention is suffocating. Survivors often describe feeling disposable, good enough for outrage, not good enough for real help. They feel used without ever having consented to their trauma becoming public property. And when the world moves on, they are left to pick up the emotional chaos unleashed by a population that treated their pain like breaking news instead of a human experience.

Long-Term Trauma Does Not Fit into Awareness Campaigns

GBV awareness campaigns often focus on dramatic messaging, statistics, and symbolic actions. They simplify the issue to make it digestible. But trauma does not simplify. It expands. It lingers. It shapes survivors’ lives years after an incident. Trauma is not an event, it is a long-term neurological and emotional reality. Survivors navigate flashbacks, nightmares, panic attacks, hypervigilance, emotional shutdowns, and identity erosion long after the violence ends. Yet awareness campaigns rarely acknowledge this because it disrupts the narrative of quick empowerment and tidy healing.

The world is comfortable supporting the beginning of a survivor’s story, the part where she speaks up, goes public, reports the abuse, or escapes. The world is much less comfortable supporting what comes after, the messy, complicated, unpredictable psychological aftermath that can stretch into years. Trauma recovery is not linear, glamorous, or instant. It includes relapses into old patterns, days where getting out of bed feels impossible, moments where self-blame resurfaces, and periods where the survivor feels like she is regressing rather than progressing. These realities clash with the inspirational tone people expect when discussing survivor stories, so they remain hidden. Survivors are left feeling like failures when their healing does not match the narrative society prefers.

Gender-Based Violence Destroys Financial Stability

One of the most devastating consequences of gender-based violence is the financial destruction it leaves behind. When the headlines fade, survivors often face a world where every aspect of their financial life has collapsed. Abusers use money as a weapon long before physical violence appears, restricting access to accounts, sabotaging careers, destroying property, isolating the victim from financial independence, or controlling work schedules. Leaving an abusive partner often means leaving behind housing, savings, assets, and stability. Survivors find themselves starting from nothing, not because they were irresponsible but because the abuser engineered their dependence.

Rebuilding financially is a long and exhausting process. Survivors suddenly face rent payments they cannot afford, school fees they cannot manage, legal costs they cannot control, and a job market they have often been disconnected from for years. Some survivors have to move back home, not because they want to, but because it is the only place they can afford. Others take low-paying jobs because they need immediate income. The financial damage also extends to credit scores ruined by debts the abuser created or by accounts the abuser controlled. Survivors face landlords who distrust them, banks who decline them, employers who judge gaps in their work history, and a system that expects them to rebuild at a pace that is impossible.

This financial fallout rarely appears in awareness conversations, yet it determines whether survivors can ever truly escape. Economic stability is safety. Without it, survivors remain vulnerable to return, re-victimisation, or further harm. Money is not separate from GBV, it is the backbone of both entrapment and recovery.

The Social Death of Speaking Out

When survivors speak publicly, they risk social death. Going public with abuse stories often results in losing friendships, alienation from family, judgment from colleagues, and backlash from entire communities. People begin to treat the survivor as though she is defined by the abuse. They see her as a cautionary tale rather than a complex human being. They question her decisions, her emotional stability, her choices, or her credibility. The abuser often becomes the beneficiary of community sympathy because he appears calm, composed, and rational, while the survivor appears emotional, distressed, or inconsistent, which is exactly how trauma manifests.

Survivors who speak out quickly learn that many people prefer them quiet. They hear comments like “Why talk about it publicly?”, “You should move on,” or “You’re making it worse.” Their honesty becomes a threat to social comfort. The abuser’s reputation is protected more fiercely than the survivor’s reality. Communities also resent the disruption that survivors create by exposing violence. Survivors force people to confront gender norms, power dynamics, and their own complicity. Many simply cannot tolerate that discomfort, so they distance themselves from the person who brought the truth into the open.

Survivors learn that speaking up costs them more than staying silent ever did. They no longer belong to the community they trusted. They become outsiders, not because they did anything wrong, but because they told the truth.

The Loneliness That Takes Over

Support for survivors is often loud in the beginning and silent in the long term. People show up with meals and messages, offers of help, and emotional support during the crisis stage. But as weeks turn into months, support dwindles. People get tired. They expect the survivor to “be better” already. They stop asking how she’s coping. They stop offering help. They assume silence means healing rather than exhaustion. They move on because they believe the worst is over.

But for survivors, the worst is often just beginning. The loneliness that follows public crisis is overwhelming. Survivors feel abandoned by the very people who pledged support. They feel guilty for still struggling. They feel ashamed that recovery is slower than others expect. They stop reaching out because they fear being a burden. They internalise the silence as proof that their trauma is too heavy for others to carry. This loneliness becomes part of the trauma, a reminder that society responds to violence, not to healing.

What It Means to Rebuild a Life

Rebuilding after gender-based violence is not a straightforward process. It requires survivors to untangle psychological conditioning, heal emotional injuries, rebuild self-worth, regain autonomy, navigate financial instability, and re-establish trust in themselves and others. The emotional landscape of recovery is unpredictable. Survivors may feel strong one day and shattered the next. They may experience intense grief for the version of themselves they lost. They may feel angry that their future was disrupted. They may feel relief that is immediately followed by guilt. They may struggle to form new relationships because fear persists long after the abuser is gone.

Rebuilding involves learning how to live without constant fear. It involves relearning what normal feels like, which is one of the most difficult adjustments. Survivors often describe struggling with silence because silence feels like the pause before violence. They struggle with kindness because kindness feels suspicious. They struggle with making decisions because they were conditioned to defer. They struggle with boundaries because boundaries were repeatedly violated. Recovery requires dismantling conditioning that took years to build. It is emotionally taxing, mentally draining, and physically exhausting.

But rebuilding is also where survivors begin to reclaim themselves. They rediscover their interests, their voice, their preferences, their instincts. They learn to listen to their bodies again. They learn to trust their thoughts again. They learn that safety is not always temporary. The process is uneven, but it is real.

Why Survivors Need Long-Term Support

Gender-based violence cannot be addressed through momentary outrage or symbolic solidarity. Survivors need long-term support that acknowledges the emotional, psychological, financial, and social impact of trauma. They need systems that do not punish them for being traumatised. They need communities that do not abandon them once the story stops trending. They need workplaces that understand trauma rather than penalise it. They need legal systems that prioritise safety over procedural convenience. They need healthcare systems that recognise trauma as an injury. They need families who do not pressure them into forgiveness. They need friends who do not withdraw when the emotional cost becomes inconvenient.

Long-term support means listening long after the story has stopped being dramatic. It means staying present through the mundane parts of healing. It means understanding that trauma does not follow a timeline that suits anyone else’s comfort. It means supporting survivors in their slow reconstruction rather than expecting them to perform strength or gratitude.

Ending GBV Requires More Than Awareness

Awareness alone does nothing to prevent gender-based violence. It only informs people that the problem exists. Real change comes from shifting the systems, cultures, and behaviours that allow violence to flourish and leave survivors alone in its aftermath. It requires communities to look beyond the headlines and recognise that gender-based violence is not a moment, it is a lifelong impact that requires lifelong support. It requires challenging the social instinct to move on quickly. It requires acknowledging that survivors cannot heal in isolation, and that true support is measured not in initial outrage but in sustained presence.

Ending gender-based violence means staying when the world leaves. It means showing up when the cameras are off. It means supporting survivors when nobody else is watching. It means choosing responsibility over convenience. And it means recognising that healing is not a story the public gets to consume, it is a process survivors must navigate, step by painful step, long after the world has forgotten the details of what happened.