Classrooms across the world are being asked to solve a problem they did not create. Children arrive at school with nervous systems shaped by constant stimulation, rapid feedback, and personalised digital content that adapts instantly to their preferences. Traditional education environments were built for sustained attention, delayed reward, shared focus, and gradual learning. These foundations now clash with brains trained for speed, novelty, and instant response. This tension is not the result of lazy students or ineffective teachers. It is the predictable outcome of a culture that has fundamentally altered how attention is formed long before formal learning begins.

Attention Has Been Retrained

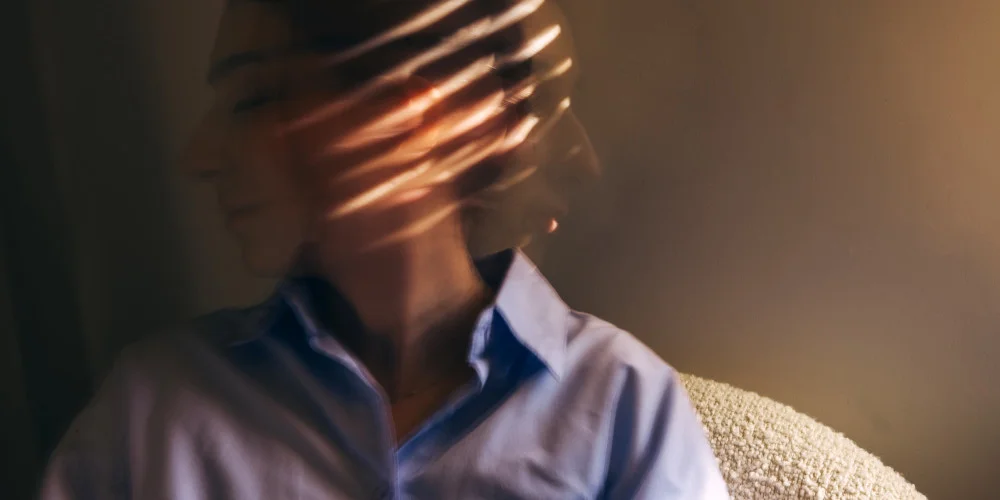

By the time many children enter their first classroom, their attention systems are already deeply conditioned. Short form videos, interactive games, endless scrolling, and instant rewards have taught the brain what engagement should feel like. Information arrives quickly, stimulation is constant, and boredom is eliminated almost entirely. When children encounter classrooms that move at a human pace, discomfort appears almost immediately. This discomfort is often misunderstood as disinterest or poor attitude when it is actually a nervous system reacting to a sudden drop in stimulation. The child is not choosing disengagement. Their brain is struggling to adjust to an environment that feels unnaturally slow compared to what it has been trained to expect.

Focus Requires Emotional Tolerance

Sustained attention is not only a cognitive skill, it is an emotional one. To focus, a child must tolerate boredom, confusion, frustration, and delayed gratification without escaping. These emotional experiences are not pleasant, but they are essential for learning. Screens remove the need to tolerate them by offering constant novelty and reward. As a result many children arrive at school with limited practice in emotional endurance. When lessons demand patience or effort without immediate payoff, frustration rises quickly. What appears as an inability to concentrate is often an inability to sit with emotional discomfort long enough for learning to occur.

Behavioural Issues Reflect Regulation Gaps

Many classroom behaviour problems are rooted in regulation rather than intention. Restlessness, impulsivity, emotional outbursts, and withdrawal often signal nervous systems that are overstimulated and struggling to downshift. In low stimulation environments, these systems feel under threat. Traditional discipline approaches focus on controlling behaviour without addressing the internal state driving it. Without understanding the role of digital conditioning, schools respond to symptoms rather than causes. This leads to cycles of punishment and resistance that solve nothing and exhaust everyone involved.

Teachers Are Asked to Compete With Algorithms

Educators are increasingly expected to compete with systems designed by teams of behavioural scientists whose sole purpose is to capture attention. Algorithms personalise content in real time, adjusting to preferences and emotional responses instantly. Classrooms cannot and should not attempt to replicate this level of stimulation. Doing so sacrifices depth, reflection, and critical thinking. Asking teachers to outperform algorithms places responsibility in the wrong place. It frames attention loss as a classroom failure instead of recognising the broader systems shaping how attention now functions.

Digital Tools Create a Double Bind

In response to declining attention, many schools increase their reliance on digital tools. Tablets, online platforms, and interactive content are introduced to engage students who are already overstimulated. While these tools can be useful in moderation, they reinforce the same patterns that undermine focus. Students become further accustomed to constant input, making non digital learning feel even more demanding. The classroom enters a feedback loop where stimulation replaces regulation, and attention capacity continues to shrink instead of recover.

Learning Becomes Shallow and Performative

When attention is fragmented, learning shifts from understanding to completion. Students focus on finishing tasks rather than engaging deeply with content. Information is consumed quickly and forgotten just as fast. Success becomes measured by output rather than comprehension. This performative learning satisfies short term metrics but undermines long term retention and critical thinking. Students may appear productive while lacking true understanding, creating gaps that surface later when deeper knowledge is required.

Emotional Safety Is Compromised

A classroom filled with dysregulated nervous systems becomes emotionally unstable. Teachers spend increasing amounts of time managing behaviour instead of teaching. Students sense tension and unpredictability, leading some to become hyper vigilant while others withdraw entirely. Emotional safety, which is essential for learning, deteriorates under constant pressure. When students do not feel emotionally secure, their capacity to focus and engage declines further, reinforcing the cycle.

Punitive Responses Miss the Root Problem

Strict discipline policies often escalate rather than resolve attention issues. Punishment does not teach regulation. It can increase shame, anxiety, and resistance. When children are punished for nervous system responses, they learn to suppress distress rather than develop coping skills. Behaviour may appear controlled temporarily, but internal regulation remains undeveloped. This approach prioritises compliance over capacity and leaves the underlying problem untouched.

Supporting Regulation Improves Learning

Classrooms that prioritise regulation see meaningful improvements in attention and behaviour. Predictable routines create safety. Movement breaks allow nervous systems to reset. Emotional literacy helps students identify and manage internal states. Reducing unnecessary digital reliance gives attention space to recover. These strategies do not lower academic standards. They make learning possible again by restoring emotional capacity.

Teachers Are Carrying an Unfair Burden

Educators are expected to fix attention problems without being given the tools or systemic support required. They are managing the downstream effects of cultural and technological shifts while being evaluated on outcomes they cannot fully control. Burnout among teachers reflects this impossible position. Supporting educators means acknowledging that the classroom cannot counteract years of digital conditioning alone.

Schools Cannot Fix This Alone

Education systems operate within broader cultural forces. Screen exposure does not stop at the school gate. Without changes at home and in society, classrooms remain overwhelmed. Collaboration between families, schools, healthcare providers, and policymakers is essential. Responsibility must be shared rather than offloaded onto teachers and children.

Winning the war for attention does not mean increasing stimulation to compete with screens. It means protecting attention as a limited and valuable resource. Education must shift away from speed and novelty and back toward depth, reflection, and regulation. This requires courage to resist trends that prioritise engagement metrics over learning quality.

Attention Is Learned and Can Be Relearned

Attention is shaped by environment, which means it can be reshaped. Children can relearn how to focus when placed in environments that support regulation rather than overwhelm it. This process takes time and consistency. It requires patience rather than punishment and understanding rather than blame.

If classrooms are to succeed, they need support rather than criticism. Attention loss is not a moral failure. It is a predictable response to modern conditions. When attention is treated as something to nurture rather than capture, learning can recover. The classroom does not need to win a war. It needs relief from one it was never meant to fight.